Pencorff noted the recent footprints.

The inventory of the objects possessed by these castaways from the sky, thrown on a coast that appeared to be uninhabited, could be promptly established.

They had nothing except for the clothes on their backs at the moment of the catastrophe. We should however mention a notebook and a watch that Gideon Spilett had saved inadvertently no doubt, but not a weapon, not a tool, not even a pocket knife. The balloon passengers had thrown everything overboard in order to lighten it. The imaginary heros of Daniel de Foe or of Wyss, as well as Selkirk and Raynal, castaways at Juan-Fernandez or the archipelago of Auckland, never found themselves so absolutely helpless. They had abundant resources drawn from their stranded vessels whether in grain, animals, tools, munitions, or else some wreckage had reached the shore which allowed them to provide for the primary needs of life. At the start they did not find themselves absolutely disarmed in the face of nature. But here, no instrument whatsoever, not a utensil. Nothing, they must obtain everything!

If however, Cyrus Smith had been with them, if the engineer had been able to put his practical science, his inventive spirit to the service of this situation, perhaps all hope would not have been lost. Alas! They could not count on seeing Cyrus Smith again. The castaways could depend on no one but themselves and on Providence who never abandons those whose faith is sincere.

But before all else should they settle themselves on this part of the shore without trying to find out what continent it belonged to, if it was inhabited or if this coast was only the beach of a deserted island?

It was an important question to be resolved with the briefest delay. The measures to be taken would depend on the answer. However it was Pencroff’s advice that it would be better to wait several days before undertaking an exploration. In fact it was necessary to prepare provisions and to obtain food more substantial than only eggs and mollusks. The explorers, having endured long fatigue, without a shelter for sleeping, would have to refresh themselves before doing anything else.

The Chimneys offered a sufficient retreat for the time being. The fire was lit and it would be easy to save the cinders. For the moment there was no lack of mollusks and eggs among the rocks and on the beach. They would surely find the means to kill some of these pigeons that flew about by the hundreds at the crest of the plateau using sticks or stones. Perhaps the trees of the nearby forest would give them edible fruit? Finally sweet water was there. It was therefore agreed that for the next few days they would remain at the Chimneys in order to prepare there for an exploration either of the coastline or of the interior of the country.

This plan particularly suited Neb. As stubborn in his ideas as in his forebodings he was in no hurry to leave this part of the coast, the scene of the catastrophe. He did not believe, he did not want to believe that Cyrus Smith was lost. No, it didn’t seem possible that such a man met his end in so vulgar a fashion, carried off by a wave, drowned in the sea only a few hundred feet from shore. As long as the waves had not thrown up the body of the engineer, as long as he, Neb, had not seen with his own eyes, touched with his own hands the corpse of his master, he would not believe that he was dead. And this idea took root in his obstinate heart more than ever. Illusion perhaps but a respected illusion nevertheless which the sailor did not wish to destroy. For him there was no more hope and the engineer had indeed perished in the waves but with Neb there was nothing to discuss. He was like a dog that will not leave the place where his master died and his grief was such that he probably would not survive him.

On the morning of March 26th, at dawn, Neb went back to the shore in a northerly direction, returning to where the sea had doubtless closed in on the unfortunate Smith.

Breakfast on this day was composed only of pigeon eggs and of lithodomes. Herbert had found some salt left behind in the crevices of the rocks by evaporation and this mineral substance was put to good use.

The meal finished, Pencroff asked the reporter if he wanted to accompany them to the forest where Herbert and he would try to hunt. However, on further reflection it was decided that someone should stay behind to look after the fire and in the unlikely event that Neb would need help. The reporter would therefore stay behind.

“To the hunt, Herbert,” said the sailor. “We will find our munitions along the way and we will fire our guns in the forest.”

But, when they were about to leave, Herbert noted that since they had no tinder it would perhaps be prudent to replace it with another substance.

“What?” asked Pencroff.

“Burnt linen,” replied the lad. “In a pinch it can serve as tinder.”

The sailor found that this advice made sense except that it was inconvenient since it meant the sacrifice of a piece of handkerchief. Nevertheless it was worth the trouble and so a piece of Pencroff’s large square handkerchief was soon reduced to a half burnt rag. This inflammable material was placed in the central chamber at the bottom of a small cavity in a rock completely sheltered from wind and dampness.

It was then nine o’clock in the morning. The weather was threatening and the wind blew from the southeast. Herbert and Pencroff turned the corner of the Chimneys not without having thrown a glance at the smoke which was twirling around from the rocks; then they went up the left bank of the river.

Arriving at the forest, Pencroff first broke off two sturdy branches which he transformed into sticks and which Herbert ground down to a point on a rock. Ah! If they only had a knife! Then the two hunters advanced among the tall grass following the riverbank. On leaving the bend that changed its course to the southwest, the river grew narrower little by little and its banks formed a channel enclosed by a double arc of trees. Pencroff, not wanting to get lost, resolved to follow the water’s course which would always return him to his starting point. But the bank was not without several obstacles, here trees whose flexible branches bent to the level of the water, there creepers or thorn bushes which they had to break with their sticks. Often Herbert glided among the broken stumps with the agility of a young cat and he disappeared into the brushwood. But Pencroff recalled him immediately begging him not to go too far.

However, the sailor carefully noted the nature of the surroundings. On the left bank the soil was level and rose imperceptibly toward the interior. Sometimes moist, it then took on a marshy appearance. Everywhere they felt an underground network of streams which, by some subterranean fault, flowed toward the river. Also at some places a brook flowed through the brushwood which they crossed without difficulty. The opposite bank seemed to be more varied and the valley, of which the river occupied the center, was more sharply patterned. The hill, covered by trees of various sizes, formed a curtain which obstructed vision. On the right bank walking would have been difficult because of the cavities in the ground and because of the trees which, curved to the surface of the water, were held in place only by their roots.

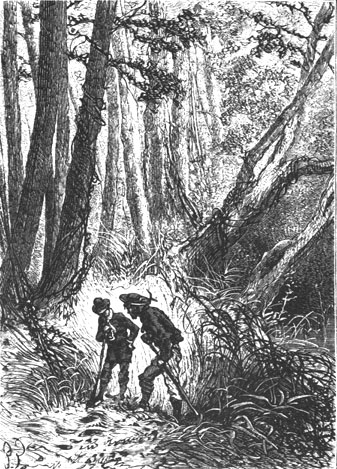

Needless to say this forest as well as the bank already travelled over, showed no sign of any human touch. Pencroff noted the recent footprints of quadrupedes of a species he did not recognize. Most certainly—and this was also Herbert’s opinion—they had been left by formidable wild beasts which they would have to contend with doubtless; but nowhere the mark of a hatchet on a tree trunk nor the remains of an extinguished fire nor a footprint. They should perhaps congratulate themselves because in this part of the Pacific the presence of man was perhaps more to be feared than desired.

Pencorff noted the recent footprints.

Herbert and Pencroff scarcely spoke because of the great difficulties along the path. They advanced very slowly and after an hour they had scarcely gone a mile. Until then the hunt had not been productive. However, several birds were chirping and flying about under the branches showing themselves to be very timid as if man instinctively inspired them with a justifiable fear. Among other winged creatures Herbert noted, in a marshy part of the forest, a bird with a sharp and elongated beak which anatomically resembled a kingfisher. However it was distinguished by its rather rugged plummage which was coated with a metallic brilliance.

“This must be a ‘Jacamar’,” said Herbert, trying to close in on the animal.

“It will be quite an occasion to taste jacamar,” replied the sailor, “if this bird is in a humor to let himself be roasted.”

At this moment a stone, skillfully and vigorously thrown by the lad, struck the creature as it was about to fly off but this was not enough because the jacamar flew away at full speed and disappeared in an instant. “How clumsy I am,” cried Herbert.

“Not at all, my boy,” replied the sailor. “It was a good throw and more than one person would have missed the bird completely. Come! Do not feel frustrated. We will catch it another day.”

The exploration continued. As the hunters made headway the trees became more spacious and magnificent but none produced any edible fruit. Pencroff looked in vain for a few of those precious palm trees which have so many uses in domestic life and which are found as far as the fortieth parallel in the northern hemisphere and down to only the thirty fifth parallel in the southern hemisphere. But this forest was composed only of conifers such as the deodars, already recognized by Herbert, of Douglas pines, resembling those growing on the northwest coast of America, and of admirable spruce measuring a hundred fifty feet in height.

At this moment a flock of small birds with a pretty plumage, with a long and sparkling tail, scattered themselves among the branches, spreading their weakly attached feathers which covered the ground with a fine down. Herbert picked up a few of these feathers and after having examined them:

“These are ‘couroucous’,” he said.

“I would prefer a guinea fowl or a grouse cock,” replied Pencroff, “but are they good to eat?”

“They are good to eat and their flesh is even tender,” replied Herbert. “Besides, if I am not mistaken, it is easy to approach them and kill them with a stick.”

The sailor and the lad glided among the grass arriving at the foot of a tree whose lower branches were covered with small birds. The couroucous were waiting for the passage of insects, which served as their nourishment. One could see their feathered feet strongly clenching the sprouts which served to support them.

The hunters then straightened themselves up and moving their sticks like a scythe, they grazed entire rows of these couroucous who did not think of flying away and stupidly allowed themselves to be beaten. A hundred littered the ground when the others decided to fly.

“Well,” said Pencroff, “here is game made for hunters such as ourselves. We have only to reach out for it.”

On a flexible stick the sailor strung up the couroucous like larks and the exploration continued. They noted that the watercourse took a gentle turn southward but this detour could not really be a prolonged one because the river’s source was in the mountain and was fed by the melting snow which covered the sides of the central cone.

The particular object of this excursion, as we know, was to procure for the hosts of the Chimneys the largest possible quantity of game. One could not say that this goal had been attained up to now. The sailor actively pursued his search and how he raved when some animal that he did not even have time to recognize, escaped among the tall grass. If only they had had the dog Top. But Top had disappeared at the same time as his master and had probably perished with him.

About three o’clock in the afternoon they caught a glimpse of new flocks of birds who were pecking at the aromatic berries of certain trees, junipers among others. Suddenly, the real sound of a trumpet was heard in the forest. It was the strange and loud fanfare made by gallinules which are called “grouse” in the United States. Soon they saw several couples, with a variety of brown and fawn colored plumage, and with a brown tail. Herbert recognized the males by the two pointed fins formed by feathers raised on their neck. Pencroff judged it indispensable to get hold of one of these gallinules, as big as a hen, and whose flesh is like that of a prairie chicken. But this was difficult because they would not allow themselves to be approached. After several fruitless attempts, which had no other result than to frighten the grouse, the sailor said to the lad:

“Decidedly, since we can’t kill them in flight, we will try to take them with a line.”

“Like a fish?” cried Herbert, very surprised at this suggestion.

“Like a fish,” the sailor replied seriously.

Pencroff found among the grass a half dozen of the grouse’s nests, each having two or three eggs. He took great care not to touch these nests to which their proprietors would not fail to return. It was around these nests that he intended to stretch his lines—not collar traps but real hook lines. He took Herbert some distance away from the nests and there he prepared his strange contraption with the care appropriate to a disciple of Isaac Walton.1 Herbert followed this activity with an interest easy to understand, while doubting its success. The lines were made of thin creepers fastened to one another to a length of fifteen to twenty feet. Some large strong thorns with bent points, furnished by a dwarf acacia bush, were tied to the ends of the creepers to take the place of hooks. As an allurement some large red worms, which were crawling on the ground, were put on the thorns.

That done, Pencroff moved among the grass skillfully concealing himself, placing the end of his lines with baited hooks near the grouse’s nests. Then he returned taking the other end and concealing himself with Herbert behind a large tree. Both then waited patiently. Herbert, it should be said, did not count much on the success of the inventive Pencroff.

A long half hour passed but, as predicted by the sailor, several couples of grouse returned to their nests. They hopped, pecked the ground, and gave no sign that they suspected the presence of the hunters who had taken care to place themselves to the leeward of the gallinules.

Certainly at this moment the lad was very attentive. He held his breath and Pencroff staring, his mouth open, his lips protruding as if he was about to taste a piece of grouse, was hardly breathing. However the gallinules walked among the hooks without noticing them. Pencroff then made small jerks which moved the bait as if the worms were still alive.

Assuredly at this moment the sailor felt an emotion greater than that of the fisherman. The latter does not see his prey approaching in the water.

The jerks soon attracted the attention of the gallinules and they pecked at the hooks. Three grouse, doubtless very voracious, swallowed both the bait and the hook. Suddenly with a quick movement, Pencroff sprung his trap and the flapping of the wings indicated to him that the birds had been taken.

“Hurrah!” he shouted, dashing toward the game which he made himself master of in an instant.

“Hurrah!” he shouted.

Herbert clapped his hands. It was the first time he had seen birds taken with a line but the sailor very modestly told him that it was not his first try and not his invention.

“And in any case,” he added, “in the situation that we find ourselves, we must depend on measures such as these.”

The grouse were tied by their feet and Pencroff, happy that he was not returning with empty hands, and seeing that the day was coming to an end, decided to return to his dwelling.

The path to follow was indicated by the river, there being no question of which direction, and at about six o’clock, rather tired from their excursion, Herbert and Pencroff again entered the Chimneys.