“Was I wrong, was I right?...”

At these words the reclining man lifted himself up and his face appeared in full light: a magnificent head, high forehead, fiery look, white beard, hair abundant and thrown back.

This man supported himself with his hands against the back of the divan. He was calm. One could see that some lingering illness was undermining him little by little but his voice still seemed strong when he said in English and in a tone which expressed extreme surprise:

“I have no name, sir.”

“I know you,” replied Cyrus Smith.

Captain Nemo fixed an ardent gaze on the engineer as if he wished to annihilate him.

Then he fell back on the pillows of the divan.

“It doesn’t matter after all,” he murmured, “I am going to die!”

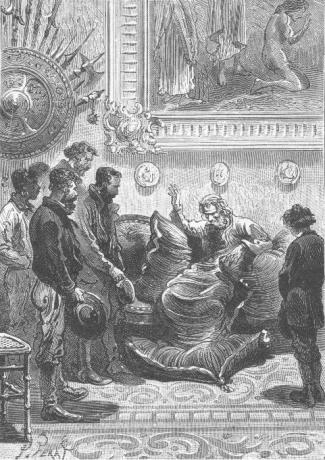

Cyrus Smith approached Captain Nemo and Gideon Spilett took his hand, which he found to be burning. Ayrton, Pencroff, Herbert and Neb respectfully stood to one side in a corner of this magnificent salon whose air was saturated with electrical radiation.

However Captain Nemo immediately removed his hand and with a sign he begged the engineer and the reporter to be seated.

All looked at him with true emotion. Here was the person they called the “genie of the island”, the powerful being whose intervention under so many circumstances had been so effective, this benefactor to whom they were so much indebted. Before their eyes there was only a man where Pencroff and Neb thought they would find a near god and this man was ready to die.

But how was it that Cyrus Smith knew Captain Nemo? Why had the latter gotten up so vividly on hearing this name pronounced which he thought the world was ignorant of?...

The captain resumed his place on the divan and, supported by his arms, he looked at the engineer seated next to him.

“You know the name which I had, sir?” he asked.

“I know it,” replied Cyrus Smith, “just as I know the name of this admirable submarine apparatus.”

“The Nautilus?” said the captain, half smiling.

“The Nautilus.”

“But do you know... do you know who I am?”

“I know that.”

“Nevertheless it has been thirty years since I have had any communication with the inhabited world, thirty years during which I lived in the depths of the sea, the only place where I found independence! Who then could have betrayed my secret?”

“A man who never pledged loyalty to you, Captain Nemo, and who consequently cannot be accused of treason.”

“The Frenchman who was cast on board by chance sixteen years ago?”

“The same.”

“This man and his companions then did not perish in the maelstrom in which the Nautilus was entangled?”

“They did not perish and a book has appeared under the title of ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea’ which contains your story.”

“The story of a few months only, sir!” replied the captain vividly.

“It is true,” replied Cyrus Smith, “but several months of this strange life have sufficed to make you known...”

“As a master criminal doubtless?” replied Captain Nemo, allowing a haughty smile to pass his lips. “Yes, a rebel, banned perhaps by humanity!”

The engineer did not reply.

“Well, sir?”

“I have not judged Captain Nemo,” replied Cyrus Smith, “at least as it concerns his past life. I am ignorant, as is all the world, of what have been the motives for this strange existence and I cannot judge the effects without knowing the causes; but this much I know, that a helping hand has always been extended to us since our arrival on Lincoln Island. We all owe our lives to a good, generous, powerful being and this powerful, generous, good being is you, Captain Nemo!”

The captain simply replied, “It is I.”

The engineer and the reporter got up. Their companions approached and the gratitude which was overflowing from their hearts was translated by gestures, by words...

Captain Nemo stopped them with a sign and with a voice doubtless more emotional than he had intended:

“Wait until you have heard me,” he said.1

And the captain, in a few clear and urgent sentences, made his entire life known.

His story was brief and yet he had to concentrate all his remaining energy to say it. It was evident that he was battling against an extreme weakness. Several times Cyrus Smith suggested that he take some rest but he shook his head, like a man who has no tomorrow, and when the reporter offered him some attention:

“It is useless,” he said, “my hours are numbered.”

Captain Nemo was an Indian, Prince Dakkar, the son of a rajah of the then independent territory of Bundelkund and a nephew of the Indian hero, Tippu-Sahib. His father sent him to Europe when he was ten years old in order that he receive a complete education with the secret intention that he would fight one day with equal arms against those whom he considered to be the oppressors of his country.

From the ages of ten to thirty, Prince Dakkar, who was superiorly endowed and of a noble heart and spirit, pursued his studies far and wide in all things, including the sciences, the letters and the arts.

Prince Dakkar travelled throughout Europe. His noble birth and his fortune made him sought after but the temptations of the world never had any attraction for him. Young and handsome, he remained serious, gloomy, ravenous in his thirst for knowledge, and having an implacable resentment riveted to his heart.

Prince Dakkar hated. He hated the only country where he never wished to set foot, the only nation whose overtures he constantly refused: he hated England and the more so because up to a point he admired it.

So it was that this Indian typified in himself all the fierce hatred of the vanquished against the conqueror. The invader would not find mercy in the invaded land. The son of one of those sovereigns from whom the United Kingdom could only expect nominal obedience, this prince from the family of Tippu-Sahib, raised on the ideas of vindication and of vengeance, having an irresistible love for his poetic country burdened by English chains, never wanted to set foot on this cursed land to which India owed its enslavement.

Prince Dakkar became an artist nobly impressed with the marvels of art, a scientist who was no stranger to advanced science, a statesman trained amongst European courts. To those who observed him casually he passed perhaps as one of those cosmopolitans, curious about knowledge, but scorning action, one of those opulent travellers with a fiery and platonic spirit who move about the world incessantly and are of no country.

This was not the case. This artist, this scientist, this man had remained Indian in his heart, Indian by his desire for vengeance, Indian by his hope of one day reclaiming the rights of his country by driving out the foreigner and restoring its independence.

Consequently Prince Dakkar returned to Bundelkund in the year 1849. He married a noble Indian woman whose heart bled as his did at her country’s misfortunes. He had two children whom he cherished. But his domestic happiness could not make him forget India’s enslavement. He waited for an occasion. It presented itself.

The English yoke weighed heavily on the Hindu population. Prince Dakkar became the spokesman for the malcontents. He instilled them with all the hatred which he felt against the foreigner. He scoured not only the still independent areas on the Indian Peninsula but also the regions directly subject to English administration. He remembered the great days of Tippu-Sahib who died heroically at Seringapatam in the defense of his country.

In 1857, the great Sepoy revolt erupted. Prince Dakkar was its soul. He organized the immense upheaval. He put his talents and his riches to the service of this cause. He sacrificed himself. He fought in the front lines, he risked his life like the humblest of those heros who had risen up to free their country; he was wounded ten times in twenty encounters but could not find death when the last soldiers of the fight for independence fell under English bullets.

Never had the English power in India been subject to such danger, and if, as they had hoped, the Sepoys had received help from the outside, it would perhaps have altered the influence and domination of the United Kingdom in Asia.

The name of Prince Dakkar was then illustrious. The heroes who supported him did not hide but fought openly. A price was put on his head and if he had not encountered a traitor to whom he entrusted his father, his mother, his wife and his children who would suffer before he realized the dangers he had caused them to undergo...

This time again, might made right. But civilization never goes backward and it seems to follow a necessary course. The Sepoys were vanquished and the land of the ancient rajahs again fell under the stricter domination of England.

Prince Dakkar, who could not find death, returned to the mountains of Bundelkund. There, henceforth alone, he was filled with disgust against all who carried the name of man, having a hatred and a horror of the civilized world and wanting to flee from it forever. He gathered the remains of his fortune, united with about twenty of his most trustworthy companions and one day they all disappeared.

Where then had Prince Dakkar gone to find this independence which the inhabited world refused him? Under the water, in the depths of the sea, where none could follow him.

The man of war became the scientist. On a deserted island in the Pacific he built a shipyard and there a submarine vessel was constructed based on his plans. By means which will one day be known, he used the incomparable force of electricity, which he drew from inexhaustible sources, for all the necessities of his floating apparatus, for movement, for lighting, and for heating. The sea, with its infinite treasures, its myriads of fish, its harvest of seaweed and sargassum, its enormous mammals, and not only everything put there by nature but also everything that mankind had lost there, would suffice amply for the needs of the prince and his crew. This was the accomplishment of his most vivid desire since he no longer wished to have any communication with the world. He named his submarine apparatus the Nautilus, he called himself Captain Nemo, and he disappeared beneath the seas.

For many years the captain visited all the oceans from one pole to the other. An outcast from the inhabited world, he gathered up admirable treasures from unknown worlds. The millions lost in the Bay of Vigo in 1702 by the Spanish galleons furnished him with an inexhaustible mine of riches which he always disposed anonymously in favor of those people who fought for the independence of their country.2

He was for a long time without any communication with his fellow beings when three men were thrown on board during the night of the 6th of November 1866. They were a French professor, his servant and a Canadian fisherman. These three men had been cast into the sea during a collision between the Nautilus and the United States frigate, the Abraham Lincoln, which was chasing it.

Captain Nemo learned from the professor that the Nautilus, sometimes taken as a giant mammal of the cetacean family, sometimes for a submarine apparatus containing a crew of pirates, was being pursued across all the seas.

Captain Nemo could have thrown back into the ocean these three men that chance had thrown across the path of his mysterious existence. He did not do that but kept them as prisoners and for seven months they were able to contemplate all the marvels of a voyage which covered twenty thousand leagues under the seas.

One day, the 22nd of June, 1867, these three men, who knew nothing of Captain Nemo’s past, succeeded in escaping after having gotten hold of the Nautilus’ boat. But since at that moment the Nautilus was trapped in a whirling maelstrom off the Norwegian coast, the captain assumed that the fugitives had drowned in the frightful eddy, finding death at the bottom of the whirlpool. He was ignorant then that the Frenchman and his two companions had been miraculously thrown on shore, that fishermen from the Lofoten Islands had saved them and that the professor, on his return to France, had published a book relating the seven months of this strange and adventurous journey of the Nautilus, indulging the public’s curiosity.

Captain Nemo still continued to live this way for a long time, following the seas. But little by little his companions died and went to their rest in their coral cemetery at the bottom of the Pacific. The Nautilus became empty and finally Captain Nemo alone remained of all those who had taken refuge with him in the depths of the ocean.

Captain Nemo was then sixty years old. Alone he succeeded in bringing his Nautilus to one of the submarine ports which he used at times.

One of these ports was hollowed out under Lincoln Island and it was this one which was now giving asylum to the Nautilus.

For six years the captain remained there, no longer navigating, awaiting death, that is to say the moment when he would be reunited with his companions when by chance he was present at the collapse of the balloon which was carrying the Southern prisoners. Putting on his diving suit, he walked under the water a few cables from shore when the engineer was thrown into the sea. On a generous impulse, the captain saved Cyrus Smith.

At first he wanted to run from these five castaways but his port of refuge was closed and as a consequence of a movement of the basalt produced by volcanic action, he could no longer pass through the entrance to the crypt. There was still enough water for a small boat to pass but no longer enough for the Nautilus which had a considerable displacement.

Captain Nemo therefore remained to observe these men, thrown without resources on a deserted island but he did not wish to be seen. Little by little, as he saw their honesty, energy and their fraternal devotion to one another, he became interested in their efforts. In spite of himself, he learned all the secrets of their existence. By means of the diving suit it was easy for him to reach the bottom of the inside well of Granite House and climb up to the upper opening, using the projections in the rock. He overheard the colonists telling about their past and discussing the present and the future. From them he learned of the immense effort to abolish slavery with American fighting American. Yes! These were men worthy of Captain Nemo’s reconciliation with the well represented humanity on the island.

Captain Nemo had saved Cyrus Smith. It was also he who brought the dog to the Chimneys, who threw Top out of the waters of the lake, who stranded at Flotsom Point this case which contained so many things useful to the colonists, who put the canoe back into the Mercy’s current, who threw down the cord from the top of Granite House when the apes attacked it, who made Ayrton’s presence on Tabor Island known by means of the document enclosed in the bottle, who capsized the brig with the explosion of a torpedo placed at the bottom of the channel, who saved Herbert from a certain death by bringing the sulphate of quinine and finally who killed the convicts with these secret electrical bullets which he used for submarine hunting. This then explained these many incidents which seemed supernatural, all of which attested to the generosity and the power of the captain.

However, the noble misanthrope still yearned to do good. There remained some useful information for him to impart to his proteges and in addition, with death approaching, he yielded to the dictates of his heart and summoned the colonists of Granite House, as we know, by means of the wire linking the corral to the Nautilus which had an alphabetical apparatus... Perhaps he would not have done it if he had known that Cyrus Smith knew enough of his history to address him by the name of Nemo.

The captain ended the story of his life. Cyrus Smith then spoke; he recalled all the incidents which had exerted such beneficial influences on the colony and in the name of his companions as well as himself, he thanked the generous being to whom they owed so much.

But Captain Nemo had no thought of putting a price on the services which he had rendered. One last thought was on his mind and before shaking the hand that the engineer presented to him:

“Now, sir,” he said, “now that you know my life, what is your judgement?”

In so speaking the captain was evidently alluding to a serious incident which had been witnessed by the three strangers thrown on board—an incident which the French professor had necessarily related in his book. The memory of it was terrible.

In fact, a few days before the professor and his two companions escaped, the Nautilus, being pursued by a frigate in the North Atlantic, had rushed against it like a battering ram and sunk it without mercy.

Cyrus Smith understood the illusion and remained silent.

“It was an English frigate, sir,” Captain Nemo shouted, again becoming Prince Dakkar for a moment, “an English frigate, do you hear me? It attacked me! I was restricted to a narrow shallow bay... I had to pass, and... I passed. ”

Then, in a calmer voice:

“I had justice and right on my side,” he added. “I always showed mercy when I could but did harm when I had to. In all fairness, isn’t that pardonable?”

A few moments of silence followed this response and Captain Nemo again asked:

“What do you think of me, gentlemen?”

Cyrus Smith held out his hand to the captain and, as requested, he replied in a solemn voice:

“Captain, your error was in believing that you could bring back the past and you have opposed necessary progress. It was one of those errors that some admire and others blame but which God alone can judge and which rational mankind must forgive. We may oppose someone who is mistaken in his good intentions, but we should not cease to esteem him. Your error is not one of those that excludes admiration and your name has nothing to fear from the judgement of history. History loves heroic madness while condemning its consequences.”

Captain Nemo’s chest heaved and he pointed to heaven.

“Was I wrong, was I right?” he murmured.

“Was I wrong, was I right?...”

Cyrus Smith replied:

“All great deeds return to God from whence they came! The honest men here, whom you have saved, will always mourn you, Captain Nemo!”

Herbert approached the captain. He bent his knees, took his hand and knelt.

A tear glistened from the eyes of the dying man.

“My child,” he said, “bless you!...”