“Nothing, sir, can induce me to give way to you on this matter.”

“I am sorry, count, but in this case your views cannot modify mine.”

“You are certain?”

“Quite certain.”

“But allow me to remind you that my seniority unquestionably gives me a prior right.”

“Mere seniority, I assert, in an affair of this kind, cannot possibly entitle you to any prior claim whatever.”

“Then, captain, no alternative is left but for me to compel you to yield at the sword’s point.”

“As you please, count; but neither sword nor pistol can force me to give way to you. Here is my card.”

“And mine.”

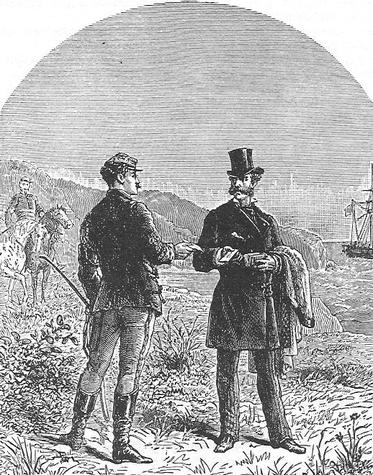

This rapid altercation was thus brought to an end by the formal interchange of the names of the disputants. On one of the cards was inscribed:

Captain Hector Servadac

Staff Officer, Mostaganem

On the other was the title:

Count Wassili Timascheff,

On board the Schooner “Dobryna”

“When and where shall my seconds meet yours?” asked Count Timascheff.

“Today, two o’clock, if that suits you,” replied Hector Servadac, “at the headquarters.”

“In Mostaganem?”

“In Mostaganem.”

And having so agreed, the captain and the count saluted one another courteously. They were about to separate when Timascheff said abruptly: “perhaps it would be better, captain, not to allow the true cause of this to transpire?”

“I agree completely,” replied Servadac.

“No names to be mentioned?”

“No names.”

“And what, then, shall be the pretext for our duel?”

“Pretext? Some musical discussion, if you have no objection, monsieur le comte.”

“Perfect,” replied Count Timascheff. “I shall take up the case of Wagner. He’s one of my favourites.”

“And I stand for Rossini, who is mine,” answered Servadac, with a smile.

And then Count Timascheff and the staff officer saluted one another once more, and finally went their separate ways.

The scene, as here depicted, took place upon the extremity of a little cape on the Algerian coast, between Mostaganem and Tenes, about two miles from the mouth of the Shelif. The headland rose more than sixty feet above the sea-level, and the azure waters of the Mediterranean, as they broke against the foot of the cliff, were tinged with the reddish hue of the ferriferous rocks that formed its base. It was the 31st of December. The noontide sun, which usually illuminated the various projections of the coast with a dazzling brightness, was hidden by a dense mass of cloud, and the fog, which for some unaccountable cause, had hung for the last two months over nearly every region in the world, causing serious interruption to traffic between continent and continent, spread its dreary veil across land and sea. But there was nothing to be done about that.

After taking leave of the staff-officer, Count Wassili Timascheff wandered down to a small creek, and took his seat in the stern of a light four-oar that had been awaiting his return. This was immediately pushed off from shore, and in a few moments it reached a pleasureyacht, that was lying to, not many cable lengths away.

At a sign from Servadac, an orderly, who had been standing at a respectful distance, led forward a magnificent Arabian horse. The captain hopped nimbly into the saddle, and followed by his attendant, who mounted a second horse almost as deftly as his master, started off towards Mostaganem.

It was half-past twelve when the two riders crossed the bridge that had been recently erected over the Shelif, and a quarter of an hour later their steeds, flecked with foam, dashed through the Mascara Gate, was one of five entrances that opened in the embattled wall encircling the town.

At that date Mostaganem was home to some fifteen thousand people, three thousand of whom were French. Besides being one of the principal district towns of the province of Oran it was also a military station. In Mostaganem one could find the finest foods, and the choicest fabrics; objects expertly woven from esparto reeds or stitched from best Moroccan leather. Many of these goods were exported to France: wheat, cotton, wool, animals of all sorts, figs and grapes. By this period all traces had long since vanished of the ancient anchorage in which, in years gone by, navies had taken shelter from the foul westerly and northwesterly gales. But the city did possess a well-sheltered harbour, which enabled her to utilize all the rich products of the Mina and the Lower Shelif.

It was the existence of so good a harbour amidst the exposed cliffs of this coast that had induced the owner of the Dobryna to winter in these parts, and for two months the Russian standard had been seen floating from her yard, whilst on her mast-head was hoisted the pennant of the Yacht Club de France, with the distinctive letters M. C. W. T., the initials of Count Timascheff.

Having entered the town, Captain Servadac made his way towards Matmore, the military quarter, and was not long in finding two friends on whom he might rely—a major of the 2nd Fusileers, and a captain of the 8th Artillery.

The two officers listened gravely enough to Servadac’s request that they would act as his seconds in an affair of honour, but could not resist a smile on hearing that the dispute between him and the count had originated in a disagreement of musical taste.

“Could we come to some arrangement?” suggested the major of the 2nd Fusileers.

“Quite impossible,” replied Hector Servadac.

“A few slight concessions on either side!” said the captain of the 8th Artillery.

“No concession is possible between Wagner and Rossini,” the staff office replied, resolutely. “It’s all or nothing. Rossini has been deeply injured. Wagner is a fool. I cannot suffer the injury to be unavenged. I am quite firm.”

“Be it so, then,” replied one of the officers; “and after all, you know, a sword-cut need not be a very serious affair.”

“Certainly not,” rejoined Servadac; “and especially for me, when I have not the slightest intention of being wounded at all.”

Incredulous as they naturally were as to the assigned cause of the quarrel, Servadac’s friends had no alternative but to accept his explanation, and without further parley they started for the staff office, where, at two o’clock precisely, they were to meet the seconds of Count Timascheff.

Two hours later they had returned. All the preliminaries had been arranged; the count, who like many Russians abroad was an aide-de-camp of the Czar, had of course proposed swords as the most appropriate weapons, and the duel was to take place on the following morning, the first of January, at nine o’clock, upon the cliff at a spot about a mile and a half from the mouth of the Shelif.

“Tomorrow, then, at nine precisely. Proper military punctuality, mind,” said the major.

“A proper military occasion in all respects,” replied Hector Servadac. The two officers cordially shook their friend’s hand and retired to the Café Zulma for a game at piquet.

Captain Servadac at once retraced his steps and left the town. For the last fortnight Servadac had not been occupying his proper lodgings in the military quarters; having been appointed to make a local levy, he had been living in a gourbi, or native hut, on the Mostaganem coast, between four and five miles from the Shelif. His orderly was his sole companion. It was very far from being luxurious, and indeed any other man than the captain would have considered so disagreeable an exile little short of a severe penance.

Now, on his way to the gourbi, Servadac’s mental occupation was a very labourious effort to put together what he was pleased to call a rondo, upon a model of versification all but obsolete. This rondo— there’s no point in trying to hide the fact—was to be an ode addressed to a young widow by whom he had been captivated, and whom he was anxious to marry, and the tenor of his muse was intended to prove that when once a man has found an object in all respects worthy of his affections, he should love her “in all simplicity.” Whether the aphorism were universally true was not very material to the gallant captain, whose sole ambition at present was to construct a roundelay of which this should be the prevailing sentiment.

“Yes, yes,” he muttered, as his orderly trotted silently beside him, “a rondo that captures this feeling would have a fine effect. They’re rare, rondos, on the Algerian coast, and mine will be better than any, I hope.”

So the poet-captain began:

In truth, whoe’er the lover be,

In all simplicity…

“That’s it! Simplicity. I want to tell her simply that I love her, and wish to marry her; but, confound it! the words won’t rhyme. Plague on it! Does nothing rhyme with ‘simplicity’? Hey, Ben Zoof!”

Ben Zoof was Captain Servadac’s orderly.

“Sir,” Ben Zoof replied.

“Did you ever compose any poetry?”

“No, captain,” answered the man promptly. “I never made any verses, but I have seen them made.”

“By whom?”

“A strange fellow at a booth, during the fete of Montmartre.”

“Can you remember them?”

“Remember them! To be sure I can. This is the way they began:”

Roll up! Come in! Come old and new!

There’s no more fun than this!

You’ll find out who’s in love with you! And who your true love is!

“Bosh! That poetry is complete rubbish.”

“Considering it was spoken through a kazoo, captain, I’d say it’s as good poetry as any others.”

“Quiet now, Ben Zoof,” said Servadac. “Quiet now. I have found my third and fourth rhymes.”

In truth, whoe’er the lover be,

In all simplicity;

Lover, loving honestly,

Offer I myself to thee.

Beyond this, however, the captain’s poetical genius was impotent to carry him. His farther efforts were unavailing, and when at six o’clock he reached the gourbi, the four lines still remained the limit of his composition.