When the schooner had approached the island, the Englishmen were able to make out the name “Dobryna” painted on the aft-board.

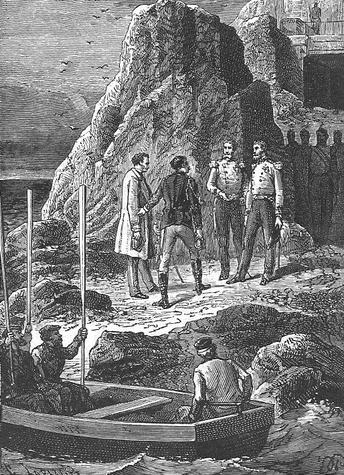

A sinuous irregularity of the coast had formed a kind of cove, which, though hardly spacious enough for a few fishing-smacks, would afford the yacht a temporary anchorage, so long as the wind did not blow violently from either west or south. Into this cove the Dobryna was duly signalled, and as soon as she was safely moored, she lowered her fouroar, and Count Timascheff and Captain Servadac made their way at once to land.

Colonel Heneage Finch Murphy and Major Sir John Temple Oliphant stood, grave and prim, formally awaiting the arrival of their visitors. Captain Servadac, with the uncontrolled vivacity natural to a Frenchman, was the first to speak.

“A joyful sight, gentlemen!” he exclaimed. “It will give us unbounded pleasure to shake hands again with some of our fellow-creatures. You, no doubt, have escaped the same disaster as ourselves.”

But the English officers, neither by word nor gesture, made the slightest acknowledgment of this familiar greeting.

“What news can you give us of France, England, or Russia?” continued Servadac, perfectly unconscious of the stolid rigidity with which his advances were received. “We are anxious to hear anything you can tell us. Have you had communications with Europe? Have you—”

“To whom have we the honour of speaking?” at last interposed Colonel Murphy, in the coldest and most measured tone, and drawing himself up to his full height.

“Ah! how stupid! I forgot,” said Servadac, with the slightest possible shrug of the shoulders; “we have not been introduced.”

Then, with a wave of his hand towards his companion, who meanwhile had exhibited a reserve hardly less than that of the British officers, he said:

“Allow me to introduce you to Count Wassili Timascheff.”

“Major Sir John Temple Oliphant,” replied the colonel.

The Russian and the Englishman mutually exchanged the stiffest of bows.

“I have the pleasure of introducing Captain Servadac,” said the count in his turn.

“And this is Colonel Heneage Finch Murphy,” was the major’s grave rejoinder.

More bows were interchanged and the ceremony brought to its due conclusion. It need hardly be said that the conversation had been carried on in French, a language which is generally known both by Russians and Englishmen—a circumstance that is probably in some measure to be accounted for by the refusal of Frenchmen to learn either Russian or English.

The formal preliminaries of etiquette being thus complete, there was no longer any obstacle to a freer intercourse. The colonel, signing to his guests to follow, led the way to the apartment occupied jointly by himself and the major, which, although only a kind of casemate hollowed in the rock, nevertheless wore a general air of comfort. Major Oliphant accompanied them, and all four having taken their seats, the conversation was commenced.

Irritated and disgusted at all the cold formalities, Hector Servadac resolved to leave all the talking to the count; and he, quite aware that the Englishmen would adhere to the fiction that they could be supposed to know nothing that had transpired previous to the introduction felt himself obliged to recapitulate matters from the very beginning.

“You must be aware, gentlemen,” began the count, “that a most singular catastrophe occurred on the 1st of January last. Its cause, its limits we have utterly failed to discover, but from the appearance of the island on which we find you here, you have evidently experienced its devastating consequences.”

The Englishmen, in silence, bowed assent.

“Captain Servadac, who accompanies me,” continued the count, “has been most severely tried by the disaster. Engaged as he was in an important mission as a staff-officer in Algeria—”

“A French colony, I believe,” interposed Major Oliphant, half shutting his eyes with an expression of supreme indifference.

Servadac was on the point of making some cutting retort, but Count Timascheff, without allowing the interruption to be noticed, calmly continued his narrative:

“It was near the mouth of the Shelif that a portion of Africa, on that eventful night, was transformed into an island which alone survived; the rest of the vast continent disappeared as completely as if it had never been.”

The announcement seemed by no means startling to the phlegmatic colonel.

“Indeed!” was all he said.

“And where were you?” asked Major Oliphant.

“I was out at sea, cruising in my yacht; hard by; and I look upon it as a miracle, and nothing less, that I and my crew escaped with our lives.”

“I congratulate you on your luck,” replied the major.

The count resumed: “it was about a month after the great disruption that I was sailing—my engine having sustained some damage in the shock—along the Algerian coast, and had the pleasure of meeting with my previous acquaintance, Captain Servadac, who was resident upon the island with his orderly, Ben Zoof.”

“Ben who?” inquired the major.

“Zoof! Ben Zoof!” exclaimed Servadac, who could scarcely shout loud enough to relieve his pent-up feelings.

Ignoring this ebullition of the captain’s spleen, the count went on to say: “Captain Servadac was naturally most anxious to get what news he could. Accordingly, he left his servant on the island in charge of his horses, and came on board the Dobryna with me. We were quite at a loss to know where we should steer, but decided to direct our course to what previously had been the east, in order that we might, if possible, discover the colony of Algeria; but of Algeria not a trace remained.”

The colonel curled his lip, insinuating only too plainly that to him it was by no means surprising that a French colony should be wanting in the element of stability. Servadac observed the supercilious look, and half rose to his feet, but, smothering his resentment, took his seat again without speaking.

“The devastation, gentlemen,” said the count, who persistently refused to recognize the Frenchman’s irritation, “everywhere was terrible and complete. Not only was Algeria lost, but there was no trace of Tunis, except one solitary rock, which was crowned by an ancient tomb of one of the kings of France—”

“Louis the Ninth, I presume,” observed the colonel.

“Saint Louis,” blurted out Servadac, savagely.

Colonel Murphy slightly smiled.

Proof against all interruption, Count Timascheff, as if he had not heard it, went on without pausing. He related how the schooner had pushed her way onwards to the south, and had reached the Gulf of Cabes; and how she had ascertained for certain that the Sahara Sea had no longer an existence.

The smile of disdain again crossed the colonel’s face; he could not conceal his opinion that such a destiny for the work of a Frenchman could be no matter of surprise.

“Our next discovery,” continued the count, “was that a new coast had been upheaved right along in front of the coast of Tripoli, the geological formation of which was altogether strange, and which extended to the north as far as the proper place of Malta.”

“And Malta,” cried Servadac, unable to control himself any longer; “Malta—town, forts, soldiers, governor, and all—has vanished just like Algeria.”

For a moment a cloud rested upon the colonel’s brow, only to give place to an expression of decided incredulity.

“The statement seems highly incredible,” he said.

“Incredible?” repeated Servadac. “Why is it that you doubt my word?” The captain’s rising wrath did not prevent the colonel from replying coolly, “Because Malta belongs to England.”

“I can’t help that,” answered Servadac, sharply; “it has gone just as utterly as if it had belonged to China.”

Colonel Murphy turned deliberately away from Servadac, and appealed to the count: “Do you not think you may have made some error, count, in reckoning the bearings of your yacht?”

“No, colonel, I am quite certain of my reckonings; and not only can I testify that Malta has disappeared, but I can affirm that a large section of the Mediterranean has been closed in by a new continent. After the most anxious investigation, we could discover only one narrow opening in all the coast, and it is by following that little channel that we have made our way hither. England, I fear, has suffered grievously by the late catastrophe. Not only has Malta been entirely lost, but of the Ionian Islands that were under England’s protection, there seems to be but little left.”

“Ay, you may depend upon it,” said Servadac, breaking in upon the conversation petulantly, “your grand resident lord high commissioner has not much to congratulate himself about in the condition of Corfu.”

The Englishmen were mystified.

“Corfu, did you say?” asked Major Oliphant.

“Yes, Corfu,” replied Servadac, with a sort of malicious triumph. “Corfou. Fou as in mad.” The officers were speechless with astonishment.

The silence of bewilderment was broken at length by Count Timascheff making inquiry whether nothing had been heard from England, either by telegraph or by any passing ship.

“No,” said the colonel; “not a ship has passed; and the cable is broken.”

“But do not the Italian telegraphs assist you?” continued the count.

“Italian! I do not comprehend you. You must mean the Spanish, surely.”

“How?” demanded Timascheff.

“Confound it!” cried the impatient Servadac. “What matters whether it be Spanish or Italian? Tell us, have you had no communication at all from Europe?—no news of any sort from London?”

“Hitherto, none whatever,” replied the colonel; adding with a stately emphasis, “but we shall be sure to have tidings from England before long.”

“Whether England is still in existence or not, I suppose,” said Servadac, in a tone of irony.

The Englishmen started simultaneously to their feet.

“England in existence?” the colonel cried. “England! Ten times more probable that France—”

“France!” shouted Servadac in a passion. “France is not an island that can be submerged; France is an integral portion of a solid continent. France, at least, is safe.”

A scene appeared inevitable, and Count Timascheff’s efforts to conciliate the excited parties were of small avail.

“You are at home here,” said Servadac, with as much calmness as he could command; “it will be advisable, I think, for this discussion to be carried on in the open air.” And hurriedly he left the room. Followed immediately by the others, he led the way to a level piece of ground, which he considered he might fairly claim as neutral territory.

“Now, gentlemen,” he began haughtily, “permit me to represent that, in spite of any loss France may have sustained in the fate of Algeria, France is ready to answer any provocation that affects her honor. Here I am the representative of my country, and here, on neutral ground—”

“Neutral ground?” objected Colonel Murphy; “I beg your pardon. This, Captain Servadac, is English territory. Do you not see the English flag?” and, as he spoke, he pointed with national pride to the British standard floating over the top of the island.

“Pshaw!” cried Servadac, with a contemptuous sneer; “that flag, you know, has been hoisted but a few short weeks.”

“That flag has floated where it is for ages,” asserted the colonel.

“An imposture!” shouted Servadac, as he stamped with rage.

Recovering his composure in a degree, he continued: “Can you suppose that I am not aware that this island on which we find you is what remains of the Ionian representative republic, over which you English exercise the right of protection, but have no claim of government?”

The colonel and the major looked at each other in amazement.

Although Count Timascheff secretly sympathized with Servadac, he had carefully refrained from taking part in the dispute; but he was on the point of interfering, when the colonel, in a greatly subdued tone, begged to be allowed to speak.

“I begin to apprehend,” he said, “that you must be laboring under some strange mistake. There is no room for questioning that the territory here is England’s—England’s by right of conquest; ceded to England by the Treaty of Utrecht. Three times, indeed—in 1727, 1779, and 1792—France and Spain have disputed our title, but always to no purpose. You are, I assure you, at the present moment, as much on English soil as if you were in London, in the middle of Trafalgar Square.”

It was now the turn of the captain and the count to look surprised. “Are we not, then, in Corfu?” they asked.

“You are at Gibraltar,” replied the colonel.

Gibraltar! The word fell like a thunderclap upon their ears. Gibraltar! the western extremity of the Mediterranean! Why, had they not been sailing persistently to the east? Could they be wrong in imagining that they had reached the Ionian Islands? What new mystery was this?

Count Timascheff was about to proceed with a more rigorous investigation, when the attention of all was arrested by a loud outcry. Turning round, they saw that the crew of the Dobryna was in hot dispute with the English soldiers. A general altercation had arisen from a disagreement between the sailor Panofka and Corporal Pim. It had transpired that the cannon-ball fired in experiment from the island had not only damaged one of the spars of the schooner, but had broken Panofka’s pipe, and, moreover, had just grazed his nose, which, for a Russian’s, was unusually long. The discussion over this mishap led to mutual recriminations, till the sailors had almost come to blows with the garrison.

Servadac was just in the mood to take Panofka’s part, which drew from Major Oliphant the remark that England could not be held responsible for any accidental injury done by her cannon, and if the Russian’s long nose came in the way of the ball, the Russian must submit to the mischance.

This was too much for Count Timascheff, and having poured out a torrent of angry invective against the English officers, he ordered his crew to embark immediately.

“We shall meet again,” said Servadac, as they pushed off from shore.

“Whenever you please,” was the cool reply.

The geographical mystery haunted the minds of both the count and the captain, and they felt they could never rest till they had ascertained what had become of their respective countries. They were glad to be on board again, that they might résumé their voyage of investigation, and in two hours were out of sight of the sole remaining fragment of Gibraltar.