Pencroff tried rubbing two pieces...

In a few words Gideon Spilett, Herbert and Neb were brought up to date. This accident which could have very serious consequences—at least Pencroff envisioned it so—produced diverse effects on the honest sailor’s companions.

Neb, in his joy at having found his master, did not listen, or rather did not even want to concern himself with what Pencroff said. Herbert, to some degree, shared the sailor’s apprehensions.

As to the reporter he simply responded to Pencroff’s words:

“By my faith, Pencroff, it’s all the same to me!”

“But I repeat to you that we no longer have any fire!”

“Pooh!”

“Nor any means of relighting it.”

“Fudge!”

“Nevertheless, Mister Spilett...”

“Isn’t Cyrus Smith here?” replied the reporter. “Isn’t our engineer alive? He will easily find the means of making us some fire, he!”

“And with what?”

“With nothing.”

What could Pencroff say? There was no reply because deep down he shared the confidence that his companions had in Cyrus Smith. The engineer was for them a microcosm composed of all the science and all human intelligence. Better to find oneself with Cyrus on a deserted island than without Cyrus in the most industrialized city of the Union. With him they could want for nothing. With him they could not despair. If someone were to tell these brave people that a volcanic eruption would annihilate this land, that this land would be thrown into the depths of the Pacific, they would have imperturbably replied: “Cyrus is here. See Cyrus!”

In the meanwhile, however, the engineer was once more plunged into a new prostration brought on by the journey and they could not call on his ingenuity at the moment. Supper was necessarily meager. In fact all the grouse meat had been eaten and there was no means whatsoever of roasting any game. Besides, the couroucous which served as a reserve had disappeared. Thus they must consider. Before anything else Cyrus Smith was transported into the central corridor. There they managed to arrange a couch of algae and seaweed that had remained almost dry. The deep sleep that took possession of him would doubtless do more to quickly bring his strength back than would any abundant nourishment.

Night came on and with it the temperature, modified by a shift in the wind from the northeast, went to freezing once more. Now, since the sea had destroyed the partitions established by Pencroff at certain points in the corridors, the air currents were re-established, which rendered the Chimneys barely habitable. The engineer would therefore have found himself in rather poor circumstances if his companions, removing a vest or a waistcoat, had not carefully covered him.

Supper this evening was composed only of the inevitable lithodomes amply gathered by Herbert and Neb on the shore. However, to these mollusks the lad added a certain quantity of edible algae that he collected on some high rocks that the sea could not reach except at times of extremely high tides. These algae belonged to the fucus family, being a species of sargassum which when dry furnishes a gelatinous material rather rich in nutrients. The reporter and his companions, after having eaten a considerable quantity of lithodomes, sucked this sargassum which they found to have a good flavor. It should be said that on Asiatic shores they are an important food for the natives.

“Never mind,” said the sailor, “it is time for Mister Smith to help us.”

However, the cold became very sharp and unfortunately they had no means of fighting it.

The sailor, truly vexed, looked for every possible way to make a fire. Neb even helped him with this. They found some dry moss and striking two pebbles they obtained some sparks but the moss, not being sufficiently flammable, did not catch. Moreover, these sparks, which were only from incandescent flint, did not have the same consistency as those which escape from a piece of steel in the ordinary tinder box. Thus the operation did not succeed.

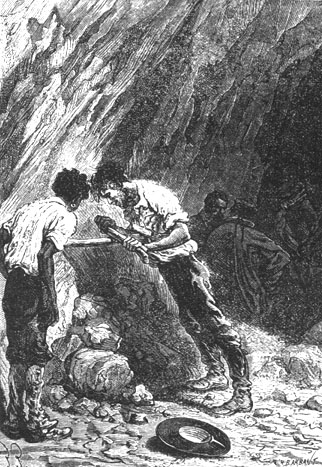

Pencroff, while having no confidence in the procedure, then tried rubbing two pieces of dry wood against each other the way the savages do. Certainly the work put in by Neb and himself, if transformed into heat according to the latest theories, would have been sufficient to heat the boiler of a steamer. The result was negative. The wood heated up, that was all, but not as much as the operators themselves.

Pencroff tried rubbing two pieces...

After working for an hour Pencroff was in a rage and he threw the pieces of wood away with spite.

“When someone can make me believe that the savages make fire in this way” he said, “it will be hot even in winter! I could sooner light up my arms by rubbing them against each other!”

The sailor was wrong in belittling this procedure. It is known that savages set fire to wood by means of a rapid rubbing. But all kinds of wood are not proper for this operation and in addition there is the “knack”, following the hallowed expression, and it is likely that Pencroff did not have the “knack.”

Pencroff’s ill humor did not last long. The two pieces of wood thrown away by him were retrieved by Herbert who did his best to rub them with renewed vigor. The robust sailor could not hold back a laugh on seeing the adolescent’s efforts to succeed where he had failed.

“Rub, my boy, rub!” he said.

“I am rubbing,” replied Herbert laughing, “but I do not pretend to do anything except take my turn at warming myself instead of shivering. Soon I will be as warm as you, Pencroff!”

That is what happened. But he had to give up on making a fire for this evening. Gideon Spilett repeated for the twentieth time that Cyrus Smith would not have been inconvenienced by such a trifle. And while waiting, he stretched out in one of the corridors on a bed of sand. Herbert, Neb and Pencroff did likewise while Top slept at the foot of his master.

The next day, March 28th, when the engineer woke up about eight o’clock in the morning he saw his companions near him watching his sleep. As on the previous day his first words were:

“Island or continent?”

One could see that he had but one idea.

“Well” replied Pencroff, “we know nothing about it, Mister Smith!”

“You still do not know?...”

“But we will know,” added Pencroff, “when you will have guided us in this land.”

“I think I’m well enough to try it,” replied the engineer who, without too much effort, got up and held himself erect.

“That’s good,” cried the sailor.

“I am dying especially of exhaustion,” replied Cyrus Smith. “My friends, a little nourishment, and it will no longer show. You have some fire, don’t you?”

This question did not get an immediate response. But after a few moments:

“Alas! We have no fire,” said Pencroff, “or rather, Mister Cyrus, we have it no longer!”

And the sailor related all that had occurred on the previous day. He enlivened the engineer with his story of the single match and of his aborted attempt to make a fire the way the savages do.

“We will think about it,” replied the engineer, “and if we do not find a substance similar to tinder...”

“Then?” asked the sailor.

“Then we will make matches.”

“With chemicals?”

“With chemicals.”

“It isn’t more difficult than that,” cried the reporter, slapping the sailor’s shoulder.

The latter did not find the thing so simple but he did not protest. They all went out. The weather was fine once again. A bright sun was rising on the sea’s horizon, striking the rugged prisms of the enormous wall with golden rays.

After having cast a quick glance around him the engineer sat down on a rock. Herbert offered him a few handfuls of mussels and seaweed saying:

“This is all that we have, Mister Cyrus.”

“Thanks, my boy,” replied Cyrus Smith, “this will suffice, for this morning at least.”

And he ate with appetite this meager nourishment which he washed down with a little fresh water drawn from the river in a large shell.

His companions looked at him without speaking. Then after satisfying himself more or less, Cyrus Smith crossed his arms saying:

“So my friends, you still do not know if fate has thrown us on a continent or on an island?”

“No, Mister Cyrus,” responded the lad.

“We will know that tomorrow,” replied the engineer. “Until then, there is nothing to do.”

“Except,” said Pencroff.

“What?”

“Fire” said the sailor, who also had only one idea.

“We will make it, Pencroff,” replied Cyrus Smith. “While you transported me yesterday didn’t I see in the west a mountain which overlooked this land?”

“Yes,” replied Gideon Spilett, “a rather high mountain...”

“Good,” replied the engineer, “tomorrow we will climb to the top and we will see if this land is an island or a continent. Until then, I repeat, there is nothing to do.”

“Yes, some fire,” said the stubborn sailor.

“But we will make fire,” replied Gideon Spilett, “a little patience, Pencroff.”

The sailor looked at Gideon Spilett as if to say: “If it depended on you to make it, we wouldn’t taste any roast soon.” But he was silent.

However, Cyrus Smith did not reply. He seemed very little preoccupied with this question of fire. For several moments he remained absorbed in his thoughts. Then he spoke again.

“My friends,” he said, “our situation is perhaps deplorable but in any case it is very simple. Either we are on a continent and then at the price of more or less fatigue we will reach some inhabited point or we are definitely on an island. In the latter case there are two possibilities: If the island is inhabited we will see to our affairs with its inhabitants: If it is deserted, we will see to our affairs all alone.”

“Nothing is simpler,” replied Pencroff.

“But be it a continent or an island,” asked Gideon Spilett, “where do you think, Cyrus, this storm has thrown us?”

“The exact location I cannot determine,” replied the engineer, “but the indications are for a land in the Pacific. In fact when we left Richmond the wind blew from the northeast and its violence even proves that its direction should not have varied. If this direction was maintained from northeast to southwest we crossed the states of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, the Gulf of Mexico, Mexico itself in its narrow part, then a portion of the Pacific Ocean. I estimate that the distance covered by the balloon was not less than six to seven thousand miles. If the wind varied by as little as an eighth it would have carried us either to the archipelago of Marquesas or to the Tuamotu, and if it had a much larger speed than I suppose, even to New Zealand. If this latter hypothesis is the case our return home will be easy. English or Maoris, we will always find someone to speak to. If, on the contrary, this shore is a part of some deserted island of a micronesian archipelago, perhaps we will recognize this from the top of the cone which overlooks this land, then we will plan on establishing ourselves here as if we will never leave it!”

“Never,” cried the reporter. “You say never, my dear Cyrus.”

“Better to first put things in the worst,” replied the engineer, “and save the surprise for the better.”

“Well spoken,” said Pencroff, “and it is also to be hoped that this island, if it is one, will not be exactly situated outside the ship lanes. That would really be a run of bad luck.”

“We will know what we have to contend with after we have first climbed the mountain,” replied the engineer.

“But tomorrow, Mister Cyrus,” asked Herbert, “will you be strong enough to make this climb?”

“I hope so,” responded the engineer, “but on the condition that Master Pencroff and you, my boy, show yourselves to be intelligent and skillful hunters.”

“Mister Cyrus,” replied the sailor, “since you are speaking of game, if, on my return, I was as certain of being able to roast it as I am of bringing it back...”

“Bring it back all the same, Pencroff,” responded Cyrus Smith.

It was thus agreed that the engineer and the reporter would spend the day at the Chimneys in order to examine the shore and the upper plateau. During this time Neb, Herbert and the sailor would return to the forest, there to renew the stockpile of wood and to lay hands on all beasts with feathers or hair that would come within their reach.

They then left about ten o’clock in the morning, Herbert confident, Neb joyful and Pencroff mumbling to himself:

“If, on my return home I find fire, I’ll believe that thunder came in person to light it.”

All three went up the bank and arrived at the bend formed by the river. The sailor stopped and said to his companions:

“Shall we begin by being hunters or woodsmen?”

“Hunters,” responded Herbert. “Top is already on the hunt.”

“Hunters then,” replied the sailor. “Then we will return here to renew our stockpile of wood.”

That said, Herbert, Neb and Pencroff, after having torn off three sticks from the trunk of a young fir tree, followed Top who dashed in among the tall grass.

This time the hunters, instead of walking along the rivercourse, plunged directly into the depths of the forest. It was always the same trees belonging for the most part to the pine family. In certain less crowded areas, isolated in clusters, these pines were very large and seemed to indicate by their development that this country was at a higher latitude than that conjectured by the engineer. Some clearings, bristling with stumps rotted by time, were covered with dead wood, and formed an inexhaustible reserve of fuel. Then, the clearing past, the brushwood grew closer and became almost impenetrable.

Without a beaten path it was rather difficult to find their way among these massive trees. Thus from time to time the sailor marked out his route by breaking some boughs that would be easy to recognize. But perhaps they were wrong not to have followed the water’s course as Herbert and he had done during their first excursion because after an hour’s march they still had no game to show. Top, moving under low branches, only gave warning of birds they could not get near. The couroucous themselves were absolutely invisible and it was likely that the sailor would be forced to return to that marshy part of the forest in which he had so fortunately used his fishing line against the grouse.

“Well, Pencroff,” said Neb in a slightly sarcastic tone of voice, “if this is all the game that you have promised to bring back to my master it will not take a big fire to roast it.”

“Patience, Neb,” responded the sailor, “it will not be the game that will be missing upon our return.”

“Have you no confidence in Mister Smith?”

“Certainly.”

“But you do not believe that he will make a fire?”

“I will believe it when the wood is burning on the hearth.”

“It will burn since my master has said so.”

“We shall see.”

However, the sun had not yet attained its highest point in its course above the horizon. The exploration therefore continued and was marked by a useful discovery, made by Herbert, of a tree whose fruit is edible. It was the pine kernel which produces an excellent almond, highly esteemed in the temperate regions of America and of Europe. These almonds were perfectly ripe and Herbert pointed this out to his two companions who were delighted by it.

“Well,” said Pencroff, “we have algae to take the place of bread, mussels for meat, and almonds for desert, what a meal for people who don’t have a single match in their pocket.”

“It’s no use complaining,” replied Herbert.

“I do not complain, my boy” said Pencroff. “Only I repeat that meat is too much economized in this type of meal.”

“Top has seen something!...” shouted Neb, who ran toward a thicket in which the dog had disappeared while barking. With Top’s barks were mingled some peculiar growls.

The sailor and Herbert followed Neb. If they had some game here this was not the time to discuss how to cook it but how to capture it.

The hunters had hardly entered the thicket when they saw Top holding an animal by an ear. This quadruped was a kind of pig about two and a half feet long, blackish brown but not as dark on the underside, having tough but thin hair. The animal’s toes, which were then gripping the ground, seemed to be united by membranes. Herbert thought he recognized this animal as a capybara, that is to say one of the largest rodents.

The hunters saw Top holding...

However, the capybara was not struggling with the dog. It stupidly rolled its large eyes which were deeply imbedded in a thick layer of fat. Perhaps it saw men for the first time.

However Neb, holding his stick firmly in his hand, went to kill the rodent when the latter, being held only by the tip of his ear, tore himself away from Top’s teeth, gave a hearty grunt, plunged headlong on Herbert, threw him half over, and disappeared through the woods.

“The rascal!” cried Pencroff.

Immediately all three darted after Top and at the moment when they rejoined him, the animal disappeared under the waters of a large pond shaded by some large old pines.

Neb, Herbert and Pencroff stopped, immobile. Top threw himself into the water but the capybara, lying at the bottom of the pond, was no longer visible.

“Let us wait,” said the lad, “because he will soon come to the surface to breath.”

“Won’t he drown?” asked Neb.

“No,” replied Herbert, “since his feet are webbed and it is almost an amphibian. But watch for him.”

Top continued to swim. Pencroff and his two companions each occupied a different point on the bank in order to cut off all retreat for the capybara which the dog was looking for while swimming on the surface of the pond.

Herbert was not mistaken. After a few minutes the animal emerged above the waters. Top was after him in a bound and prevented him from plunging again. An instant later the capybara, dragged to the bank, was killed by a blow from Neb’s stick.

“Hurrah!” cried Pencroff, who gladly used this cry of triumph. “If we could only get a hot fire this rodent will be gnawed to the bone.”

Pencroff loaded the capybara on his shoulder and judging by the height of the sun that it was about two o’clock, he gave the signal to return.

Top’s instinct was not useless to the hunters who, thanks to the intelligent animal, were able to find the road already traveled on. A half hour later they arrived at the bend in the river.

As he had done the first time, Pencroff quickly made a raft of wood, even though for want of a fire it seemed like a useless task, and with the raft moving downstream, they returned to the Chimneys.

But the sailor had not gone fifty steps when he stopped, let out a new formidable hurrah, and pointing to the corner of the cliff:

“Herbert! Neb! Look!” he shouted.

“Herbert! Neb! Look!” shouted Pencroff.

Smoke was escaping and twirling above the rocks!