It was a piece of strong cloth.

Cyrus Smith and his companions slept like innocent marmots in the cavern which the jaguar had so politely left at their disposal.

At sunrise all were on the shore at the very extremity of the promontory, looking toward the horizon which was visible for two thirds of its circumference. For one last time the engineer could confirm that no sail, no remains of a vessel appeared on the sea, and the telescope did not show anything suspicious.

Neither was there anything on the shore, at least on the straight part that formed the southern coastline of the promontory for a distance of three miles, because beyond, an indentation of land concealed the remainder of the shore and even at the extremity of Serpentine Peninsula they could not see Cape Claw, hidden by high rocks.

The rest of the southern shore of the island remained to be explored. Now, should they try to undertake this exploration immediately and devote this day of November 1st to it?

This was not in their original plan. In fact when the canoe was abandoned at the sources of the Mercy, it had been agreed that after having observed the western coast, they would return to it and go back to Granite House via the Mercy. At the time Cyrus Smith believed that the western shore could offer a refuge either to boat in distress or to a vessel on its regular course; but from the moment that the coast showed no landing place, it became necessary to search the south of the island to find there what they had not been able to find in the west.

It was Gideon Spilett who proposed to continue the exploration so that the question of the presumed wreck could be completely resolved. He asked at what distance Cape Claw could be from the extremity of the peninsula.

“About thirty miles,” replied the engineer, “if we take into account the curvature of the coast.”

“Thirty miles!” replied Gideon Spilett. “That will be a good day’s march. Nevertheless I think that we should return to Granite House by the southern shore.”

“But,” noted Herbert, “it is at least another ten miles from Cape Claw to Granite House.”

“Make it forty miles in all,” replied the reporter, “and let us not hesitate to do it. At least we will have observed this unknown coast and we will not have to undertake this exploration again.”

“Quite right,” Pencroff then said. “But the canoe?”

“The canoe has remained alone for one day at the sources of the Mercy,” replied Gideon Spilett. “It can stay there just as well for two days. For the moment we can hardly say that the island is infested with thieves.”

“However,” said the sailor, “when I recall the story of the tortoise, I no longer have that confidence.”

“The tortoise! The tortoise!” replied the reporter. “Don’t you know that it was the sea that turned it over?”

“Who knows?” murmured the engineer.

“But...” said Neb.

It was evident that Neb had something to say because he opened his mouth to speak but nothing came out.

“What did you want to say, Neb?” the engineer asked him.

“If we return via the shore to Cape Claw,” replied Neb, “after having doubled the cape, we will be stopped...”

“By the Mercy!” replied Herbert, “and in fact, we will have neither a bridge nor a boat with which to cross it!”

“Fine, Mister Cyrus,” replied Pencroff, “with a few floating trunks we will not be inconvenienced in crossing the river.”

“That’s not important,” said Gideon Spilett, “it will be useful to construct a bridge if we want to have easy access to the Far West.”

“A bridge!” cried Pencroff. “Well, isn’t Mister Smith the best engineer in his profession? But he will make us a bridge when we want to have a bridge. As to transporting you this evening to the other side of the Mercy without wetting a stitch of your clothing, I’ll be responsible for that. We still have a day’s provisions and that is all that we need and besides, we may have more game today than we had yesterday. Let’s go!”

The reporter’s proposition, very vividly supported by the sailor, gained general approval because everyone wanted to settle his doubts and by returning via Cape Claw, the exploration would be complete. But there wasn’t an hour to lose because forty miles was a long trip and they could not count on reaching Granite House before night.

At six o’clock in the morning the small troop was on its way. As a precaution against any undesirable encounters with animals on two or four feet, the guns were loaded with ball and Top, who was in the lead, was ordered to scour the edge of the forest.

On leaving the extremity of the promontory which formed the tail of the peninsula, the coast was rounded for a distance of five miles, which was rapidly crossed without the most minute investigations having shown the least trace of a landing either in the past or recently, neither a wreck nor the remainder of an encampment nor the cinders of an extinct fire nor a footprint.

The colonists arrived at the corner where the curvature of the coast ended. They were then able to extend their view to the northeast over Washington Bay and over the entire extent of the southern shore of the island. Twenty five miles away the coast ended at Cape Claw which was slightly blurred by the morning fog. A mirage made it seem suspended between land and sea. Between the spot occupied by the colonists and the beginning of the immense bay, the shore was composed of a very smooth and flat beach bordered by trees. Further along, the shore became very irregular with sharp points projecting into the sea, and finally several blackish rocks were piled up in picturesque disorder ending at Cape Claw.

Such was the development of this part of the island that the explorers saw for the first time. They quickly surveyed it after having stopped for a moment.

“A vessel that would put in here,” Pencroff said, “would inevitably be lost. This beach of sand extends up to the sea and the reefs beyond! Dangerous waters!”

“But a least something of this vessel would remain,” the reporter noted.

“Some pieces of wood would remain on the reefs but nothing on the sand,” replied the sailor.

“Why so?”

“Because the sand is even more dangerous than the rocks, engulfing everything that is thrown upon it and only a few days would be needed for the hull of a vessel of several hundred tons to disappear there entirely!”

“So, Pencroff,” asked the engineer, “if a vessel ran aground on these banks, it is not astonishing that there is no longer any trace of it?”

“No, Mister Smith, with the aid of time or tempest. Still, it would be surprising, even in this case, if some debris of the masts and spars were not thrown on the bank beyond the reach of the sea.”

“Let us then continue our search,” replied Cyrus Smith.

An hour after noon the colonists arrived at the beginning of Washington Bay and at this time they had covered a distance of twenty miles.

They halted for lunch.

There the coast became bizarrely irregular and was covered by a long line of reefs behind which were banks of sand. The tide was low at the moment but would not be long in covering it. They saw the supple waves of the sea breaking against the tops of rocks, and then turning into long foam fringes. From this point up to Cape Claw, there was little space for the beach which was confined between the edge of reefs and that of the forest.

The trip thus became more difficult because of the innumerable rocks which encumbered the shore. The granite wall also tended to become higher as they went on and they could see only the green tops of trees that crowned it, not disturbed by any wind.

After resting for a half hour, the colonists again took to the road and no point on the reefs or beach escaped their attention. Pencroff and Neb even ventured among the reefs anytime some object attracted their attention. But there was no wreck and they were misled by some bizarre shape of rocks. They did note however, that edible shellfish abounded in these waters but they could not profitably exploit this until communication would be established between the two banks of the Mercy and also when the means of transport would be perfected.

There was no indication of the presumed wreck on this shore notwithstanding that fact that the hull of a vessel was an object of some importance and should have been visible. Some of the debris should have carried to shore, as had the case found at least twenty miles further on, but there was nothing here.

About three o’clock, Cyrus Smith and his companions arrived at a narrow, well enclosed inlet which was not associated with a watercourse. It formed a real small natural port, invisible from the sea, which could be reached by a narrow passage between the reefs.

At the rear of this inlet some violent convulsion had torn up the rocky shore and an excavation on a gentle slope gave access to the upper plateau. This was situated at least ten miles from Cape Claw and consequently four miles in a straight line from Grand View Plateau.

Gideon Spilett proposed to his companions that they halt here. They accepted because the trip had sharpened everyone’s appetite and, though it was not dinner time, no one could refuse a piece of venison. This meal would permit them to wait for supper at Granite House.

A few minutes later, the colonists were seated at the foot of a magnificent cluster of maritime pines, devouring the food that Neb had taken from his knapsack.

This spot was fifty or sixty feet above the level of the sea. The radius of their view was rather extended, passing over the last rocks of the cape and into Union Bay. But neither the islet nor Grand View Plateau was visible, nor could it be from that position because the level of the ground and the screen of trees abruptly masked the northern horizon.

Needless to say, in spite of the expanse of sea that could be seen by the explorers, and as much as the engineer’s telescope swept from point to point across this entire circle on which the sky and water blended, no vessel was seen.

Likewise on all this part of the shore that still remained for exploration, the telescope swept with the same care from the beach to the reefs, but no wreck appeared within the field of view of the instrument.

“Come,” said Gideon Spilett, “we must resign ourselves to the inevitable and take comfort in the thought that no one will come to dispute our possession of Lincoln Island.”

“But what about the lead bullet!” said Herbert. “It still wasn’t imagined, I suppose.”

“A thousand devils, no!” cried Pencroff, thinking of his missing molar.

“Then what can we conclude?” asked the reporter.

“This,” replied the engineer, “that in the last three months at most, a vessel, voluntarily or not, landed...”

“What! You admit, Cyrus, that it was engulfed without leaving any trace?” cried the reporter.

“No, my dear Spilett, but note that it is certain that a human being has set foot on this island and it appears none the less certain that he has now left it.”

“Then if I understand you, Mister Cyrus,” said Herbert, “the vessel went away?...”

“Evidently.”

“And we have lost a chance to leave?” said Neb.

“Past all hope, I’m afraid.”

“Well! Since the chance is lost, let us be on our way,” said Pencroff, who was already homesick for Granite House.

But hardly had he gotten up when Top came out of the woods barking loudly and holding in his mouth a scrap of cloth soiled with mud.

Neb tore this scrap from the dog’s mouth. It was a piece of strong cloth.

It was a piece of strong cloth.

Top continued to bark and by his coming and going he seemed to invite his master to follow him into the forest.

“Here is something which may explain my lead bullet!” cried Pencroff.

“A castaway” replied Herbert.

“Wounded perhaps!” said Neb.

“Or dead!” replied the reporter.

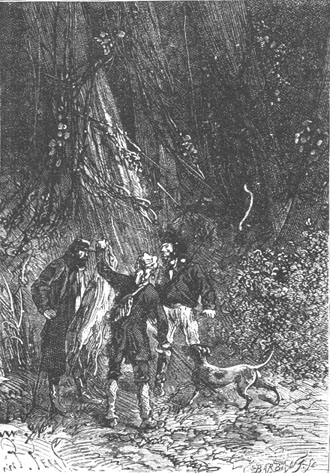

And everyone followed the dog among the large pines which formed the first screen of the forest. Cyrus Smith and his companions loaded their guns for any eventuality.

They had to advance rather deeply into the woods but to their great disappointment, they still did not see any footprints. Brushwood and creepers were intact and it was even necessary to cut them with the axe as they had done in the thickest part of the forest. It was thus difficult to admit that a human creature had already passed there. Still Top came and went, not as a dog who searched at random, but as a being endowed with a will, who is following up an idea.

After seven or eight minutes, Top stopped. The colonists arrived at a sort of clearing bordered by large trees. They looked around but saw nothing either under the brushwood or among the tree trunks.

“But what is it, Top?” asked Cyrus Smith.

Top barked louder jumping to the foot of a gigantic tree.

Suddenly Pencroff cried:

“Ah! Fine! Ah! Perfect!”

“What is it?” asked Gideon Spilett.

“We are looking for a wreck on sea or on land!”

“Well?”

“Well, it is to be found in the sky!”

And the sailor pointed to a sort of huge white cloth hanging on to the top of a pine, of which Top had brought a piece that had fallen to the ground.

“But this is not a wreck,” cried Gideon Spilett.

“I beg your pardon!” replied Pencroff.

“Indeed. It is...”

“It is all that remains of our aerial boat, of our balloon which is stranded up there at the top of this tree.”

Pencroff was not mistaken and he let out a magnificent hurrah and added:

“There is good cloth! It will furnish us with linen for years. With this we can make handkerchiefs and shirts! Hey! Mister Spilett, what do you think of an island where shirts grow on trees?”

It was truly a happy circumstance for the colonists of Lincoln Island that the balloon, after having made its last leap into the sky, fell back again on the island, and that they had this chance to find it. Either they could keep the envelope in its present form if they wanted to attempt another escape by air, or they could profitably use these several hundred yards of cotton cloth of good quality, after removing the varnish. Pencroff’s joy in thinking about this was unanimously and vividly shared.

But it was necessary to take this envelope from the tree on which it was hanging, to put it in a secure place, and this was no small job. Neb, Herbert and the sailor, having climbed to the top of the tree, had to use all their dexterity to disengage the enormous deflated balloon.

The operation lasted nearly two hours and not only the envelope with its valves, its springs, its copper trimmings, but the rope, that is to say the considerable cordage, the retaining ring and the anchor of the balloon were brought down. The envelope, except for the fracture, was in good condition, and only its lower portion was torn.

The operation lasted nearly two hours.

It was a fortune that had fallen from the sky.

“All the same, Mister Cyrus,” said the sailor, “if we ever decide to leave the island, it will not be in a balloon, will it? They do not go where one wants, these vessels of the sky, and we know something about that! Take my word, we will build a good boat of about twenty tons and you’ll allow me to cut a foresail and a jib out of this cloth. As to the rest, it will serve to clothe us.”

“We will see, Pencroff,” replied Cyrus Smith, “we will see.”

“While waiting, we must put it all in a safe place,” said Neb.

In fact, they could not think of transporting this load of cloth and cordage, whose weight was considerable, to Granite House. While waiting for a convenient vehicle to cart it, it was important not to leave these riches any longer to the mercy of the first storm. The colonists, uniting their efforts, succeeded in dragging everything to the shore where they discovered a rather large rocky cavern which would be visited neither by the wind nor the rain nor the sea thanks to its orientation.

“It is proper to have a wardrobe. We have a wardrobe,” said Pencroff, “but since it does not close with a key, it would be prudent to conceal the opening. I do not say this for two footed thieves but for thieves on four feet.”

At six o’clock in the evening all was stored. After having given the justified name of “Port Balloon” to this small indentation which formed the cove, they were back on the road to Cape Claw. Pencroff and the engineer chatted about various projects which it would be convenient to put into execution with the briefest delay. Before anything else, it was necessary to throw a bridge over the Mercy in order to establish easy communication with the south of the island; then the cart would come back to look for the balloon since the canoe would not suffice to transport it; then they would construct a decked boat, then, Pencroff rigging it as a cutter, they could undertake some voyages around the island, then, etc.

However, night came on and the sky was already dark when the colonists reached Cape Claw in the very same place where they had discovered the precious case. But there, as everywhere else, there was nothing to indicate any wreck whatsoever. They had to go back to the conclusion previously made by Cyrus Smith.

From Cape Claw to Granite House there still remained four miles which were rapidly crossed. It was after midnight when, after having followed the shore up to the mouth of the Mercy, the colonists arrived at the first bend formed by the river.

There the bed measured eighty feet in width and it was a difficult crossing but Pencroff, having made himself responsible for overcoming this difficulty, could not change his mind.

They had to admit that they were exhausted. The day’s march had been a long one and the incident of the balloon had not rested their arms and their legs. They were therefore in a hurry to get back to Granite House, to eat and to sleep and if a bridge had been constructed they would have found themselves in their dwelling in a quarter of an hour.

It was very dark. Pencroff then prepared to keep his promise by making a sort of raft that could cross the Mercy. Neb and he, armed with axes, chose two trees near the bank with which they counted on making the raft. They began to chop away.

Cyrus Smith and Gideon Spilett, seated on the bank, were waiting for the time when they could help their companions, while Herbert came and went without digressing far.

Suddenly the lad, who had ascended the river, came running back and pointing upstream:

“What is that floating there?” he cried.

Pencroff interrupted his work and vaguely saw a moving object in the shadows.

“A canoe!” he said.

All approached and saw, to their extreme surprise, a boat moving in the stream.

“Oh! A canoe!” cried the sailor in a lapse of caution, without thinking if it would perhaps be better to keep silent.

No answer. The boat still drifted. It was not more than a dozen feet away when the sailor cried:

“But it is our canoe! It broke its mooring and followed the current. It certainly arrived in the nick of time.”

“Our canoe?...” murmured the engineer.

Pencroff was right. It really was the canoe, whose mooring had doubtless broken and which had returned all alone from the sources of the Mercy. It was thus important to seize it before it was dragged beyond the mouth by the rapid current of the river. That is what Neb and Pencroff skillfully did by means of a long pole.

The canoe was brought to the shore. The engineer, being the first to embark, seized the mooring and assured himself, by fingering it, that the mooring had really worn away by rubbing against the rocks.

“That is what can be called a circumstance...,” the reporter said to him in a low voice.

“Strange!” replied Cyrus Smith.

Strange or not, it was fortunate. Herbert, the reporter, Neb and Pencroff embarked in their turn. There was no doubt that the mooring had worn away, but the most astonishing thing about the affair truly was that the canoe had arrived just at the moment when the colonists could seize it in passing, because a quarter of an hour later it would have been lost at sea.

If they had lived in the time of genies, this incident would have given them the right to think that the island was haunted by a supernatural being who placed his power at the service of the castaways.

A few strokes of the oar brought the colonists to the mouth of the Mercy. The canoe was towed to the beach at the Chimneys and everyone went toward the ladder of Granite House.

But at this moment Top barked in anger and Neb, who was looking for the first rung, let out a cry...

The ladder was no longer there.